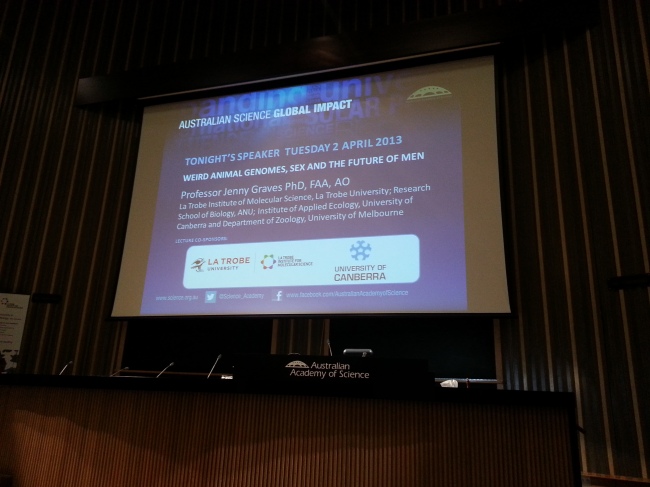

In further adventures into public lectures, this evening I attended a lecture run at the Questacon Technology Learning Centre (QTLC). For those who don’t know, Questacon is the National Science and Technology Centre in Australia – and it’s really awesome. The Questacon Technology Learning Centre is kind of an offshoot of Questacon. It contains the workshop, where they build all the exhibits for the centre, but also a workshop area where classes or groups can have… well… workshops, where you can build things for yourself.

But today we were at QTLC for a public lecture as part of the lecture series “Torque – Revolving Ideas”. And today’s lecturer was Dr Graham Walker, rather well known around the SciComm circuit for his science shows. However, lecture is a bit of a misleading word in this case. In this environment you could be forgiven for thinking your ‘lecture’ was you chatting to a friend while sitting in your backyard shed.

This lecture was much more in my comfort zone content-wise than yesterday. Having a background in Science Communication, as well as spending this year doing science shows in schools around the country, I found Dr Walker’s lecture not only interesting but also helpful for my own work.

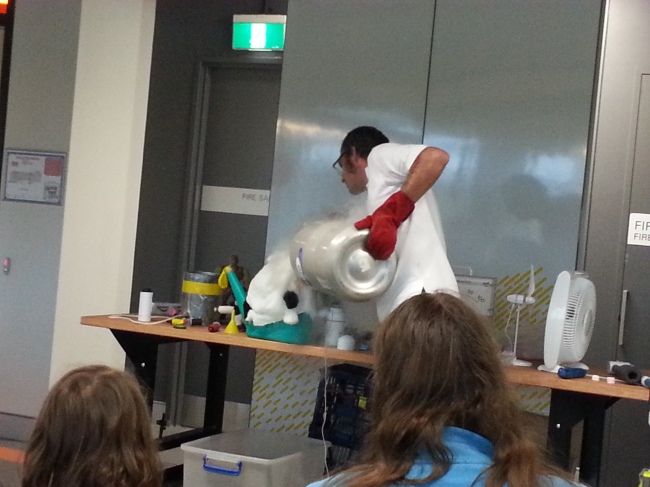

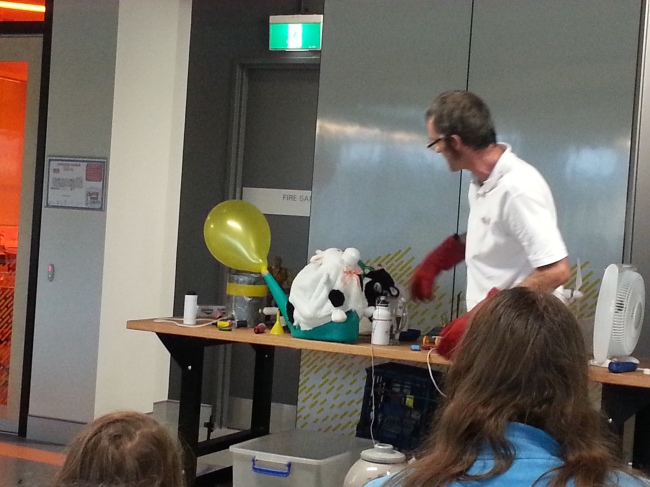

Dr Walker’s talk focused around the evolution of his props for his demonstrations over time. An example of this I loved was a demonstration about the formation of gases by cows. To our delight, he did this by blowing up balloons (attached to containers made up to look like cows) to simulate the production of methane. Dr Walker’s props had evolved from a small cow toy with a tube protruding from its behind, to a cow toy sitting on its hind legs with a (deflated) balloon attached to its mouth. The balloon, filled with bicarb soda, was then tipped over into the stomach of the cow which contained vinegar, causing the balloon to inflate with carbon dioxide. A simple reaction, with a visually appealing result. Dr Walker then proceeded onto a cow constructed from a watering can in which he exploded a balloon using liquid nitrogen.

Liquid nitrogen cow…

Just before the balloon exploded…

These demonstrations raised a few important points.

Firstly, the importance of analogies in demonstrations. In these demonstrations, the cows were producing carbon dioxide or nitrogen gas depending on the demo. Cows produce predominantly methane, so it’s important to recognise the analogies and the limitations of all demonstrations lest the audience get the wrong message – the last thing you want in science communication.

Secondly, it highlighted the importance of always working on improving your props. Even if you think they’re fantastic, work on them. Play with them. See if you can make them better. As Dr Walker pointed out, a lot of good can come from tinkering. And a lot of good can come from plain old luck – you never know when your playing could make a demonstration that is better in new and exciting ways, or could demonstrate a completely new concept.

But on the flipside, the next thing to know was when to keep innovating or start from scratch and when to use other people’s ideas and build on them. After all, so much of science is building on previous work and making it better or taking it further. Isaac Newton’s quote “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” was mentioned in addition to this. I have often been encouraged to use this method when developing my own science shows, some demonstrations are tried and tested and work well with audiences. Don’t feel bad about using other people’s demonstrations, building on them or making them your own. It’s all contributing to the field of science communication and education and it’s what they’re there for.

And I feel this post should conclude in a similar manner to that of the lecture. With a hovercraft. Before riding his hovercraft across the room, Dr Walker mentioned that he’d intended on adding a catapult to it before getting caught up in more tempting projects. To which my only response was: what’s more tempting than a catapult on a hovercraft?

(It’s rather difficult to take a good photo of a person on a moving hovercraft, especially when you’re laughing as hard as I was)